The Washington Post today published an investigation showing that US-origin software is central to China’s hypersonic missile development. This is part of a broader trend in which US originated technology, including semiconductors, have been exported to key strategic end uses in China. This includes the export of processors that are being used in computational work by Chinese military and strategic entities.

These cases are part of a broader pattern in which US technologies and know-how are being acquired by Chinese strategic entities. CNS has identified Chinese (and Russian) trends in technology acquisition as recently published. See here.

China acquires technology from the US in several ways, including:

- Procurement of non-listed goods through distributors, as occurred in this case

- The acquisition of technology through university and technology partnerships (including those that take place outside of the US but still receive American technology)

- The acquisition of technology through cybertheft, including coordinated hacking and phishing efforts

- The acquisition of expertise through recruitment of academics and researchers working in advanced technology fields

- The use of front companies based in Hong Kong or other territories subject to fewer trade restrictions

- The acquisition of companies in the US or third-party countries which have had access to US technology

The US has a robust system of export controls. However, these recent cases highlight systematic limitations of US export control policy related to China that need to be addressed. These include:

- For non-listed technology (i.e. EAR 99), companies do not need to seek licenses unless a known party to the transaction is a listed entity, or the company knows or has been informed that the technology will be used for a missile or nuclear end use.

- Such unlisted goods are often sold through third parties and distributors with the US company not knowing the true end use, or without proper due diligence. This encourages companies to ‘self-blind’. In this case, the US-based seller told the Washington Post they did not ensure their Chinese distributor counterparty was not selling to military entities “because they promised me [they would not] and I trust them, so I don’t do this kind of tracking”. Where the distributor is based in China, the recent cases provide evidence that Western companies do not always ensure that end users are not listed entities.

- There are likely also cases in which controlled goods are sold through distributors in this way without end users being known. Unless the US company and US government have confidence that they have visibility of the end users of exports through distributors in regions of concern, licenses should not be granted for such cases.

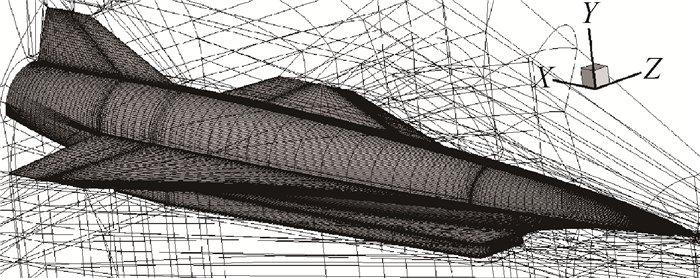

- The US should introduce a new unliteral control (and encourage other likeminded countries to do the same) that makes licensable software capable or marketed for the modelling and development of supersonic and hypersonic aircraft. While it is recognized that this approach, to including ‘marketed’, differs from the usual criteria-driven approach to controlling technologies under the international regimes, this approach should be considered as a way of capturing otherwise unlisted and difficult to define software that can be used for hypersonic missile development. In practice, it also affords software developers a mechanism to exempt their software from export control (i.e. by restricting it in such a way that it cannot be used for hypersonic use cases without approval).

- The US should introduce a new broad-based military catchall control applicable in relation to China. While the US does have catchall controls related to missile and nuclear applications, it does not presently have a broad-based military catchall control that requires companies to seek licenses when they know that the end use is military. Instead, current US regulations allow the Department of Commerce to inform companies that a license is required for non-listed items destined for a military end use. This has the effect of disincentivizing companies to report trade with military-related entities.

- The US should require technology holders to implement some form of cybersecurity standard around export-controlled information. It makes no sense to control the export of technology if the same technology is left unsecured on a company’s server at home. Companies in turn should set out how they ensure the cybersecurity of export-controlled information as part of their internal compliance program or at the time of audit. In this particular case, the Ansys representative interviewed noted that “piracy has unfortunately become an industry wide problem” when suggesting that the software used by China had no record of sale with Ansys. Adequate cybersecurity standards are necessary to prevent these illicit exchanges.

- Not all entities of concern appear on the US military end user list or end user list. The US should move quickly to expand these lists to include all entities involved in military, strategic, and space applications in China. The US should consider moving to a ‘license required’ approach for exports to any of the major Chinese strategic and defense conglomerates.

It will be important also for other countries with similar technology status to adopt these measures. Presently, most countries do not publish lists of entities of concern in China, meaning that only the catchall controls (as opposed to entity-based restrictions) that would be applicable for unlisted items. A number of key jurisdictions have broader scope catchall controls related to China because China is under a full-scope arms embargo; this includes the EU and the UK. Outreach efforts should focus on expanding the adoption of military and strategic entity catchall controls in other jurisdictions and on ensuring that all jurisdictions leverage these tools to restrict exports to military and strategic entities in China.